CMMC vs. NIST SP 800-171 … and Then Some

Posted on December 13, 2019 by Christopher Bukowski

Intro

Over the last couple of years there has been some confusion about the relatively new cybersecurity compliance standards which the Department of Defense (DOD) has implemented for its contractors, specifically under NIST SP 800-171. The regulations and standards established were seemingly sudden and somewhat ambiguous regarding what exactly, if anything, the contractor was obliged to adhere to. Though the DOD was, and still is, trying to hedge against an unprecedented amount of cybersecurity threats targeting it and its contractors, these new rules seemed to raise more questions than provide answers.

The DOD is now attempting to address this confusion, while also streamlining the cybersecurity compliance process, with its much-anticipated Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) framework, expected to be released in January 2020. This new framework will attempt to answer many, if not all, these questions by clarifying the requirements and making them more specific to the individual contracts, based on the type, nature and sensitivity of the work. The CMMC framework includes 5 levels of certification, ranging from basic cyber hygiene to highly advanced practices. Furthermore, this new system will provide the DOD with better assurance that these protocols are being fully implemented, since third-party assessors will be verifying the cybersecurity postures, as opposed to the self-attestation that NIST SP 800-171 allows.

Given these different sets of frameworks, this article attempts to give a brief overview of exactly what rules are now applicable, how they apply to contractors and how they relate to each other (or, for that matter, differ).

Origin Story

To help get some perspective, let’s briefly review the developmental history of both NIST SP 800-171 and CMMC compliance requirements and their common goals.

In May of 2008, President Bush issued a Memorandum for the Designating and Sharing of Controlled Unclassified Information:

This memorandum (a) adopts, defines, and institutes “Controlled Unclassified Information” (CUI) as the single, categorical designation henceforth throughout the executive branch for all information within the scope of that definition… and (b) establishes a corresponding new CUI Framework for designating, marking, safeguarding, and disseminating information designated as CUI. The memorandum’s purpose is to standardize practices and thereby improve the sharing of information, not to classify or declassify new or additional information. [i]

This memorandum was later rescinded by President Obama’s Executive Order 13556 Controlled Unclassified Information in November 2010 [ii], which broadened the scope of the original memorandum.

The primary purpose of both orders was to centralize and protect all of the different types of sensitive, but unclassified, government information under the same program, while also providing unified procedures for identifying, classifying, marking, handling and storing them. Ultimately, the intent was to provide a simpler way to deal with the various types of sensitive, but unclassified, information with the hopes that this unification would lead to better inter-agency communication, a reduction in the miscategorization of information and result in better protection but simpler handling procedures.

A few examples of information under the umbrella of CUI include, but are not limited to, For Official Use Only (FOUO), Controlled Technical Information (CTI) and Covered Defense Information (CDI).

For the DOD, at least, the culmination of these efforts resulted in the CUI Registry [iii] which is maintained by the National Archives, the regulatory adoption of Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) 52.204-21 – Basic Safeguarding of Covered Contractor Information Systems in June 2016 [iv] and Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) 252.204-7012 – Safeguarding Covered Defense Information and Cyber Incident Reporting in October 2016 [v].

As prescribed by FAR 4.1903 [vi], FAR 52.204-21 is applicable to any contract when the “contractor or a subcontractor at any tier may have Federal contract information residing in or transiting through its information system”.

DFARS 252.204-7012 has an even broader scope of applicability, as prescribed by DFARS 204.7302 [vii], stating that “contractors and subcontractors are required to provide adequate security on all covered contractor information systems”.

A “covered contractor information system” is “an unclassified information system that is owned, or operated by or for, a contractor and that possesses, stores, or transmits covered CDI”. The clause goes on to state that “the contractor shall implement NIST SP 800-171 [viii], as soon as practical, but not later than December 31, 2017”.

Furthermore, DFARS 252.204-7008 states “by submission of this offer, the Offeror represents that it will implement the security requirements specified by NIST SP 800-171”.

These two DFARS clauses not only require that DOD contractors with covered contractor information systems become NIST SP 800-171 compliant but also state, essentially by default in continued work and proposals to the DOD, that they are self-certifying and represent that they are NIST SP 800-171 compliant.

In summary, the FAR has as its end goal the application of basic safeguarding requirements, while the DFARS clauses go a step further and require full NIST SP 800-171 compliance. According to the regulations, contractors with covered systems are required to be compliant with the NIST standard and, by continued proposals and work with the DOD, represent and/or certify themselves as such.

More details about the history and application of CUI, the regulatory requirements and NIST SP 800-171 can be found in a recent blog by Brigham Slocum: CMMC, CUI and DoD Contractors [ix].

Supporting the common goal of a more robust cybersecurity posture across the US government and industry, in May of 2017 President Trump signed Executive Order 13800, “Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure” [x]. President Trump’s EO resulted in an update to the National Cyber Strategy of the US in September 2018 [xi], which, in turn, led to the 2018 update to the DOD Cyber Strategy [xii].

In short, the updated 2018 DOD Cyber Strategy raised the bar from the self-representation or certification provided for by the FAR and DFARS clauses by collaborating to “strengthen the cybersecurity and resilience of DOD, DCI [Defense Critical Infrastructure], DIB [Defense Industrial Base] networks and systems” [xiii]. The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition & Sustainment goes on to state that “The CMMC is intended to serve as a verification mechanism to ensure appropriate levels of cybersecurity practices and processes are in place to ensure basic cyber hygiene as well as protect controlled unclassified information (CUI) that resides on the Department’s industry partners’ networks.” [xiv]

The new CMMC framework is anticipated to drop in January 2020, be incorporated into RFIs by June 2020, in all RFQs/RFPs by September 2020 and fully implemented across all DOD Contracts within 3 years. Though the DOD has given some basic information about CMMC – i.e. there will be 5 levels to it, it will be required of all DOD contractors, it will not allow POA&Ms – much of the information out there now regarding CMMC is speculation.

CMMC is yet another iteration of a cybersecurity framework and compliance posture that DOD contractors must adhere to in order to protect CUI and Federal Contract Information (FCI). In addition to the items mentioned above, we know that CMMC is going to be a contract requirement (at least initially), rather than a regulatory requirement, in order to help implement the process as quickly as possible. Another difference is that CMMC is going to be verified through a third-party assessor rather than self-attestation.

More Questions

Now that CMMC is rolling out, there seems to be a lot of misunderstanding out there that the CMMC framework will be replacing the NIST SP 800-171 requirements or that the NIST framework can now be ignored. Is this the case? Can we now ignore or dismiss the NIST SP 800-171 requirements? The rest of this article will attempt to address whether or not this is the case (at least as far as we know at this point) and, if not, what exactly is required.

Basic Rules

FAR 52.2014-21 requires a general and basic cybersecurity posture of its DOD contractors. NIST SP 800-171 is another regulatory requirement provided for primarily in DFARS 252.204-7012 and goes a step further by requiring a self-attestation as to the contractor’s compliance with the controls. A contractor’s continued proposal submission and support of DOD contracts seems to presume continued representation of NIST SP 800-171 compliance.

Additionally, although the DOD will not audit your compliance with NIST SP 800-171 controls, it does expect that the self-attestations be grounded in truth. This can be seen in the fact that there is precedent currently being set in the courts, under the broad applicability of the False Claims Act, revealing that contractors can be held liable for false claims of NIST SP 800-171 compliance.

Furthermore, the “Christian Doctrine” is a legal doctrine applicable to contracts subject to the FAR that was established in the case of G.L. Christian and Associates v. United States (1963) [xv]. In a nutshell, the doctrine states that “standard clauses” found in the FAR (i.e., prescribed in the FAR as applicable to all contracts of the same type of contract in question) that are “a deeply ingrained strand of public procurement policy” should be “incorporated into it [the contract] by operation of law”, even if the specific clause isn’t actually in a particular contract regardless of whether or not it’s absence is by mistake or by design (intentional).

As applied to the FAR and DFARS regulations in question, the Christian Doctrine may very well be applicable, meaning that even if the specific clauses are not in the contract, the NIST SP 800-171 compliance still may be a requirement if the contractor has a “covered contractor information system”. The regulations seem to meet both of the elements required for the Doctrine to apply, since they are “standard clauses” applicable to all contracts with “covered contractor information systems” and are “deeply engrained in public procurement policy” (i.e., protection of sensitive DOD information).

On the other hand, CMMC will be a contractual requirement which will eventually be implemented into all DOD Contracts and require an objective third-party assessment at regular intervals thereafter.

Both the FAR/DFARs and CMMC are/will be obligatory as regulatory and contract requirements, respectively. Furthermore, there has been no indication thus far that the contractual requirements of third-party assessments for CMMC will replace the regulatory requirements for self-attestation of NIST SP 800-171 implementation.

Analysis

Presumably, complying with the NIST SP 800-171 requirements would fulfill the FAR requirements as well since the NIST framework provides for a general and basic cybersecurity posture as required by the FAR. For our purposes then, NIST SP 800-171 compliance would fulfill the requirements of both the FAR and DFARS.

Though CMMC and NIST SP 800-171 are similar in nature and share a common goal – the protection of CUI – they are not the same.

First, CMMC has 5 levels of compliance, depending on the sensitivity of the information in any given contract, whereas NIST SP 800-171 has one basic level with an additional supplement for enhanced protections (NIST SP 800-171B).

CMMC is going to be a contractual requirement while NIST SP 800-171 is a regulatory requirement.

Furthermore, CMMC will require a third-party assessor while NIST SP 800-171 only requires self-attestation.

CMMC will assess the cybersecurity controls of the company like NIST SP 800-171 does, but “will also assess the company’s maturity/institutionalization of cybersecurity practices and processes” [xvi].

Finally, the CMMC framework combines “various cybersecurity control standards such as NIST SP 800-171, NIST SP 800-53, ISO 27001, ISO 27032, AIA NAS9933 and others into one unified standard for cybersecurity” [xvii]. CMMC, for the most part, will utilize NIST SP 800-171 as a building block, among others, for its framework.

In summation, once CMMC gets fully implemented, it will require DOD contractors be certified to the appropriate CMMC level by an objective third-party assessor, and then re-certified at regular intervals thereafter. So far, nothing has stated that CMMC will be replacing the regulatory requirements for NIST SP 800-171 and the self-representation/certification required therein, that is, there has been no indication that one framework will be replacing or trumping the other.

Application

What does all this mean in practicality? Simply put, contractors may be bound to comply with both NIST SP 800-171 and CMMC if they have both the contractual and regulatory requirements applicable to them.

Though the 2 frameworks have a lot of similarities and even overlap each other in large part, there are distinctions that must be addressed, if both are required. The indications thus far are that CMMC level 3 will roughly match the basic NIST SP 800-171 requirements, with a few additional controls provided for in the CMMC framework.

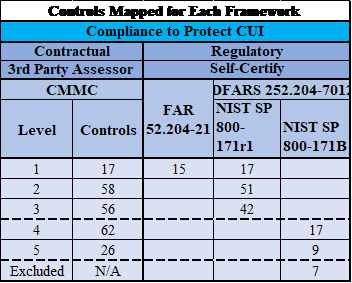

The image below provides a rough idea of the anticipated controls per CMMC level and how they map to NIST SP 800-171, FAR and DFARS clauses.

As far as we can tell, at this point, this means that if a contractor has a CMMC level 3 requirement in a contract and can be successfully certified at that level, they will likely be compliant with the NIST SP 800-171 as well. Conversely, if the contractor were fully compliant with the NIST framework, they still would not be fully compliant with CMMC level 3.

However, if the contractor has a particular contract that requires a CMMC level 2, but also has a DFARS regulatory requirement flowed down, which obliges them to be NIST SP 800-171 compliant, the contractor must abide by both framework requirements since a CMMC level 2 certification will not fulfill the NIST requirement. Initially one might simply think that, in a case like this, the more stringent of the requirements, namely NIST, would fulfill the CMMC requirements, so the contractor can just comply with NIST and pass their CMMC level 2 audit. However, that is not necessarily the case, since as it stands now, there are certain practices (deltas) required at CMMC Level 2 that are not required in NIST SP 800-171. So, the contractor truly will need to implement each.

If the contractor had a CMMC level 1 requirement as well as a NIST SP 800-171 requirement, then fulfilling the NIST requirement would ostensibly fulfill the CMMC level 1 requirement; however, the reverse circumstances would not fulfill the NIST requirement.

As stated previously, a CMMC level 1, 2 or 3 compliant system and/or a NIST SP 800-171 compliant system would presumably fulfill the requirements found in the FAR.

For these purposes we are not specifically addressing CMMC levels 4 and 5 or NIST SP 800-171B as they involve advanced cybersecurity postures.

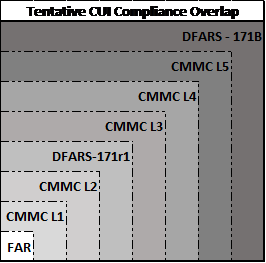

The table below shows the tentative levels of cybersecurity compliance and how they overlap each other (keep in mind, the table below only rates the levels below based on the number of controls they have, however, the different levels may not totally overlap the requirements of all the controls in the levels below it).

This table attempts to show the tentative relationships and overlap between the different levels of both frameworks and how a contractor might go about complying with both requirements. This is a simplistic view of how the different frameworks and levels may relate to each other based on the number of controls each one has. Again, keep in mind that some levels may not completely overlap the ones below it as there may be additional controls or differences in controls in the lower levels that are not required in the higher level).

For instance, if Contractor A was a software developer and had a DFARS requirement for NIST SP 800-171 compliance as well as a contractual requirement to be CMMC level 3 compliant, then CMMC level 3 would presumably fulfill both requirements. However, it is important to keep in mind, as stated above, that the reverse is not true, i.e. NIST SP 800-171 compliance will not fulfill CMMC level 3 or even level 2, for that matter.

On the other hand, if a company mowing lawns at a military base had a CMMC level 1 requirement and FAR requirement, but no DFARS requirement, then presumably the CMMC level one compliance would fulfill both requirements.

However, if that same lawnmowing company also had a DFARS NIST SP 800-171 requirement, this could become the default standard of compliance since it is the highest of the applicable frameworks and encompasses all the controls required at the lower levels (or CMMC level 3 which is even higher on the scale). If they had a CMMC level 2 requirement as well as the NIST requirement then they would have to default to both frameworks since neither of the requirements completely fulfill the requirements of the other.

Contractors should remember to be aware of the Christian Doctrine as. Just because a specific FAR or DFARS clause is not in a particular contract, it does not necessarily mean that it is not applicable. If it is a typical clause applicable to contracts of the same nature (e.g., all “covered contractor information systems”) and has a “deeply engrained strand of public procurement policy” behind it (which the cybersecurity posture of industry systems would seem to be) then it is still applicable.

Contractors must also be aware of the liability they could incur under the False Claims Act. This isn’t something that should be taken lightly and when self-assessing for NIST SP 800-171 compliance they should be honest and ensure that their program is up to speed with its requirements.

Conclusion

Contractors should not just assume that they are off the hook for their NIST SP 800-171 compliance requirements because they are being assessed, and even certified, at a CMMC level. They should check to see if the FAR and DFARS regulations apply to them (whether flown down in the contract or by operation of law through the Christian Doctrine) and, since all DOD contractors will eventually have to be CMMC compliant to one level or another, check to see which level of compliance they need for the contract.

All contractors should take these requirements seriously as well because if they are not complaint with NIST SP 800-171 when they should be, they may be liable via the False Claims Act. Likewise, if they aren’t compliant with CMMC to the standard required by a contract they will not even be able to have their proposal considered for award nor subsequently added to the contract without the certification.

Once they have determined their obligations regarding these requirements, they should review the requirements and compare them to find the similarities and deltas, if any exist. Once this has been completed, it likely would be most efficient to pick the more rigorous requirement and implement those controls while also tracking any delta controls that may need to be accommodated for in the other requirement (remember CMMC level 3 will ensure NIST 800-171 compliance, but not vice versa).

Contractors may find the best course of action to be retention of an outside consultant who can evaluate their current security posture, show them their deficiencies and even mitigate those deficiencies in order to pass the certification process (whether by third party for CMMC or self-attestation for NIST or both).

Furthermore, since recertification is going to be a continual process it may be worthwhile to retain those consultants between recertifications in order to ensure continued security posture compliance throughout the lifecycle of the certification and help ensure recertification, when the time comes. In most cases, this would not necessitate thousands of dollars a month in expenditures to simply maintain the necessary posture and would add extensive value by curbing unnecessary risk which could result in the loss of time, money, PR, etc.

Moreover, if the contractor is bound by both requirements it may be prudent not only to have the consultant help the contractor pass their CMMC requirements but also provide help in becoming NIST SP 800-171 complaint; additionally, that consultant could provide an objective third party affirmation of the contractors NIST compliance and help bolster and confirm their self-attestation to the government, which could considerably reduce the risk associated with being found non-compliant with the NIST framework.

Ultimately, in many cases, the best course of action would be to retain a trusted third party consultant to assess, mitigate and help facilitate the CMMC certification process and, likewise to comply with the NIST requirements, attest to that compliance and maintain the basic cybersecurity posture throughout the lifecycle of the certification and recertification process.

*This article is based on opinion, nothing in this article is meant to give legal advice of any kind.

[i] https://fas.org/sgp/bush/cui.html

[ii] https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2010/11/04/executive-order-13556-controlled-unclassified-information

[iii] https://www.archives.gov/cui

[iv] https://www.acquisition.gov/content/part-52-solicitation-provisions-and-contract-clauses#id1669B0A0E67

[v] https://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/dars/dfars/html/current/252204.htm

[vi] https://www.acquisition.gov/content/part-4-administrative-and-information-matters#i4_1903

[vii] https://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/dars/dfars/html/current/204_73.htm

[viii] https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-171/rev-1/final

[ix] https://bluemantletech.com/cui-cmmc-and-dod-contractors/

[x] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-executive-order-strengthening-cybersecurity-federal-networks-critical-infrastructure/

[xi] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/National-Cyber-Strategy.pdf

[xii] https://media.defense.gov/2018/Sep/18/2002041658/-1/-1/1/CYBER_STRATEGY_SUMMARY_FINAL.PDF

[xiii] https://media.defense.gov/2018/Sep/18/2002041658/-1/-1/1/CYBER_STRATEGY_SUMMARY_FINAL.PDF

https://www.acq.osd.mil/cmmc/faq.html

[xiv] https://www.acq.osd.mil/cmmc/faq.html

[xv] https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/312/418/53812/

[xvi] https://www.acq.osd.mil/cmmc/faq.html

[xvii] https://www.acq.osd.mil/cmmc/faq.html